Born in China, Beijing in 1981, Wu Qiong graduated from the Beijing Shi Fan University in 2001 and Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts in 2006. He was exposed to art very young in life with his father being an artist and his mother being a fashion designer.

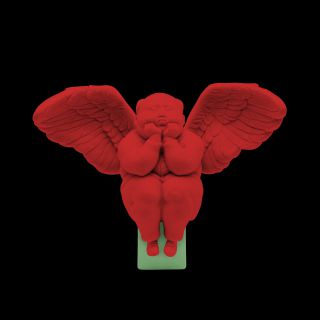

Wu Qiong’s art focuses on childhood, capturing a nostalgic and sometimes humorous portrayal of a generation's childhood experiences. Inspired by China and Singapore, his post-Pop art blends elements of Pop Art with a more personal and nostalgic touch. His experiences growing up in the 1980s under the one-child policy also influences his creations.

Wu Qiong’s art has garnered attention internationally and in China, though his collector are typically kept private. His art has also been exhibited at various international fairs including Art Miami, Art Cologne and Bridge Art Fair.

Important Collections:

Musée des Beaux-Arts de Tours, France

Asian Art Museum of Cuba, Cuba

Daniel Yun, Founder & Managing Director at MediaCorp Raintree Pictures, Singapore

Watson Tan, Founder of Upfront Models, Singapore

Sally Teo, Chief Fashion Editor at ACP Magazines, Singapore

Addy Lee, Celebrity Stylist, Singapore

Mark Lee, Artiste at MediaCorp, Singapore

Quan Yi Fong, Artiste at MediaCorp, Singapore

Ben Yeo, Artiste at MediaCorp, Singapore

Malaysia Embassy, Singapore

Wu Qiong’s art focuses on childhood, capturing a nostalgic and sometimes humorous portrayal of a generation's childhood experiences. Inspired by China and Singapore, his post-Pop art blends elements of Pop Art with a more personal and nostalgic touch. His experiences growing up in the 1980s under the one-child policy also influences his creations.

Wu Qiong’s art has garnered attention internationally and in China, though his collector are typically kept private. His art has also been exhibited at various international fairs including Art Miami, Art Cologne and Bridge Art Fair.

Important Collections:

Musée des Beaux-Arts de Tours, France

Asian Art Museum of Cuba, Cuba

Daniel Yun, Founder & Managing Director at MediaCorp Raintree Pictures, Singapore

Watson Tan, Founder of Upfront Models, Singapore

Sally Teo, Chief Fashion Editor at ACP Magazines, Singapore

Addy Lee, Celebrity Stylist, Singapore

Mark Lee, Artiste at MediaCorp, Singapore

Quan Yi Fong, Artiste at MediaCorp, Singapore

Ben Yeo, Artiste at MediaCorp, Singapore

Malaysia Embassy, Singapore

Videos

Videos

Publications

Publications

Biography

Biography

Wu Qiong was born in Beijing, China in 1981. He graduated from the Beijing Shi Fan University in 2001 and Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts in 2006. Both sculptor and painter, Wu creates art that represents the childhood that he and many others of his generation remembered and in doing so, creates touching and amusing portraits of childhood that are distinctly contemporary in the Chinese art scene. Acclaimed both internationally and locally, Wu Qiong has participated in various international art fairs, including Art Miami, Art Cologne and Bridge Art Fair.

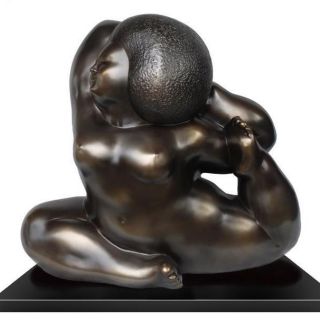

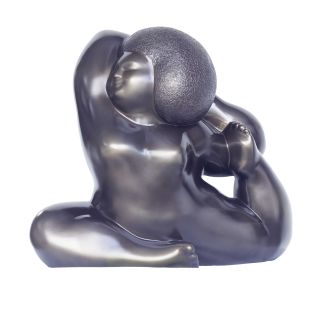

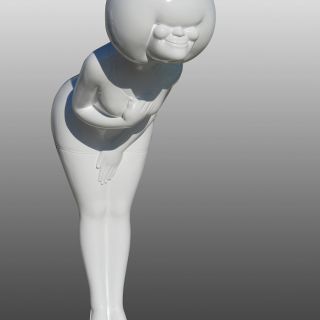

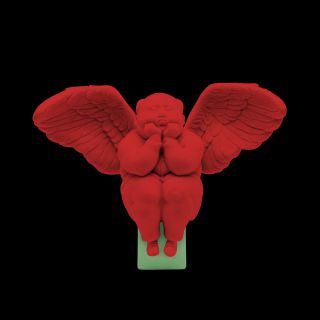

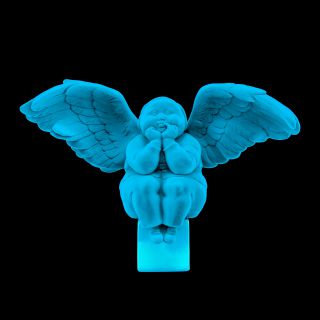

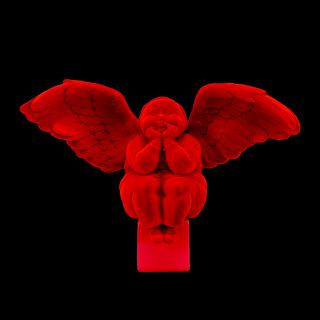

In his art, Wu Qiong often represents children coming to terms with the world of adulthood, but still remaining distinctly childlike; a suggestion that part of us never truly lets go of childhood. This concept is furthered by the innocent expressions on the faces of his sculptures and paint subjects, which are a great part of their appeal. Sometimes his characters march to tunes in their heads, or take to the air amidst fluffy white clouds. At other times, they come to terms with reality - which possibly symbolizes the artist - along with his alter egos in the guise of children - having woken up to the way life really is.

The artist's fairytale visions of childlike figures against stark backgrounds and pastel skies sets him apart from his contemporaries. His work makes 'political stress release' and cynicism, ideals which were once so characteristic of contemporary Chinese art, seem generations away. It is perhaps this contrast that reflects the economic leaps of his generation. It is difficult to criticize the agents of modern change in China, economic development and liberalization, but it is also too simple to describe Wu's paintings as celebrations. In fact, his style bears resemblance to the 'cartoon' painting of Guangdong Province in the 1960s, which expressed a political stand against Beijing's cultural hegemony. In 21st century China, Wu resonates with the cartoon aesthetic of a generation absorbed by comic imagery, online gaming and computer worlds. It may seem relatively idyllic, but as Wu points out, "the artists born of this generation have been accused of being part of a shallow culture - as though they should apologize for not having been born into the turmoil and chaos that previous generations suffered." No generation is without its hardships and there is a passionate realism in Wu's works that is present above the humour.

In his more recent works, Qiong's cartoon form appears more mature than previous social representations, indulging in a personal celebration of archetype and subject. The limelight of a generation of privileged children that once expressed yells of frustration along with self-absorbed smiles has now been stolen by internationally renowned celebrities. Perhaps Wu's latest works are saying that his generation, as it has enjoyed the fruits of its parents' labours, has also seen China rise admirably onto the international stage.

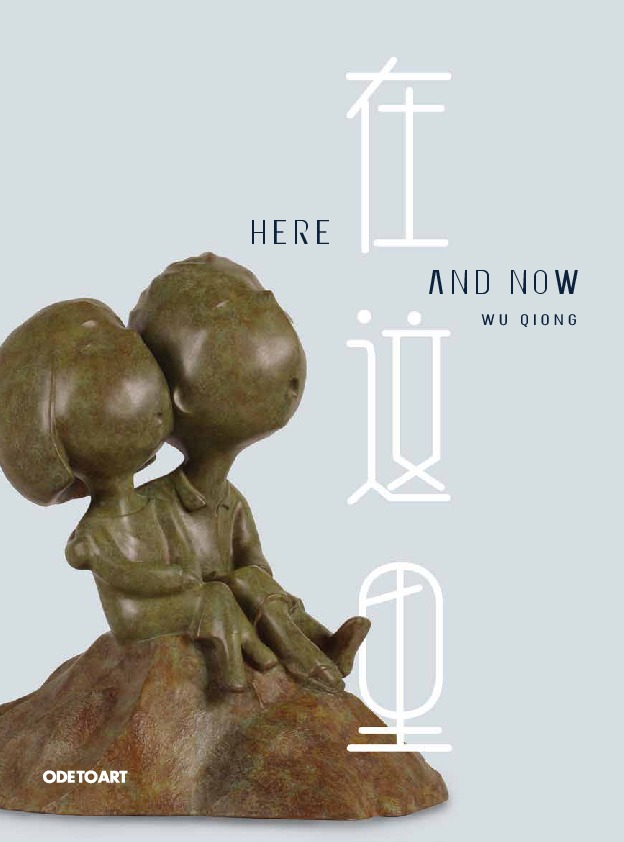

In Here: The Newest Series by Wu Qiong

Making a bold departure from his previous series featuring his characteristic children and their idealistic upturned faces, Wu Qiong further explores the metastasis of his core conceptual theme of generations, creating starkly older figures carrying the same expression of preoccupation and blissful ignorance. Using both sculpture and canvas to beautifully capture the descriptive features of an older couple, the artist dresses his characters in a garb of maturity, exuding an older world charm without either flamboyance or dourness. The conceptual commentary, with regard to his previous series, crosses the generational divide to address the displacement experienced by both young and old alike, further expanding on the artist’s belief that no generation is without hardship, and that each carries its very own identity of thought, appearance and behaviour.

Toning down his fiery sunsets and vibrant hues into melancholy softness, the artist further displays his technical prowess on canvas by seamlessly integrating gradients and exemplifying his representative skill of both human and animal form. Carrying a wistful, almost magical atmosphere of fantastical painterly worlds, the emotion behind his art remains as palpable as ever. Now hinting at more poignant moments and communicating concepts that move beyond the generational gap, Wu Qiong’s art moves firmly from the nostalgic world of children into the ever-changing, ever-reflective present reality.

Important Collections

Musée des Beaux-Arts de Tours (Museum of Fine Arts of Tours), Tours, France

(Sculpture) Asian Art Museum of Cuba (Prints)

Managing Director and Founder of MediaCorp Raintree Pictures (Singapore), Daniel Yun (Oil Painting)

MediaCorp artiste Mark Lee, Singapore (Sculpture, Oil Painting, Prints)

Celebrity Stylist, Addy Lee, Singapore (Sculpture, Oil Painting, Prints)

Founder of Upfront Models modeling agency, Watson Tan (Sculpture, Oil Painting)

ACP Magazines (Cleo, Women’s Weekly) Chief Fashion Editor, Sally Teo (Oil Painting)

Television host and MediaCorp artiste, Quan Yi Fong (Oil Painting)

Television host and MediaCorp artiste, Ben Yeo (Oil Painting)

Malaysia Singapore embassy in Malaysia (Oil Painting)

In his art, Wu Qiong often represents children coming to terms with the world of adulthood, but still remaining distinctly childlike; a suggestion that part of us never truly lets go of childhood. This concept is furthered by the innocent expressions on the faces of his sculptures and paint subjects, which are a great part of their appeal. Sometimes his characters march to tunes in their heads, or take to the air amidst fluffy white clouds. At other times, they come to terms with reality - which possibly symbolizes the artist - along with his alter egos in the guise of children - having woken up to the way life really is.

The artist's fairytale visions of childlike figures against stark backgrounds and pastel skies sets him apart from his contemporaries. His work makes 'political stress release' and cynicism, ideals which were once so characteristic of contemporary Chinese art, seem generations away. It is perhaps this contrast that reflects the economic leaps of his generation. It is difficult to criticize the agents of modern change in China, economic development and liberalization, but it is also too simple to describe Wu's paintings as celebrations. In fact, his style bears resemblance to the 'cartoon' painting of Guangdong Province in the 1960s, which expressed a political stand against Beijing's cultural hegemony. In 21st century China, Wu resonates with the cartoon aesthetic of a generation absorbed by comic imagery, online gaming and computer worlds. It may seem relatively idyllic, but as Wu points out, "the artists born of this generation have been accused of being part of a shallow culture - as though they should apologize for not having been born into the turmoil and chaos that previous generations suffered." No generation is without its hardships and there is a passionate realism in Wu's works that is present above the humour.

In his more recent works, Qiong's cartoon form appears more mature than previous social representations, indulging in a personal celebration of archetype and subject. The limelight of a generation of privileged children that once expressed yells of frustration along with self-absorbed smiles has now been stolen by internationally renowned celebrities. Perhaps Wu's latest works are saying that his generation, as it has enjoyed the fruits of its parents' labours, has also seen China rise admirably onto the international stage.

In Here: The Newest Series by Wu Qiong

Making a bold departure from his previous series featuring his characteristic children and their idealistic upturned faces, Wu Qiong further explores the metastasis of his core conceptual theme of generations, creating starkly older figures carrying the same expression of preoccupation and blissful ignorance. Using both sculpture and canvas to beautifully capture the descriptive features of an older couple, the artist dresses his characters in a garb of maturity, exuding an older world charm without either flamboyance or dourness. The conceptual commentary, with regard to his previous series, crosses the generational divide to address the displacement experienced by both young and old alike, further expanding on the artist’s belief that no generation is without hardship, and that each carries its very own identity of thought, appearance and behaviour.

Toning down his fiery sunsets and vibrant hues into melancholy softness, the artist further displays his technical prowess on canvas by seamlessly integrating gradients and exemplifying his representative skill of both human and animal form. Carrying a wistful, almost magical atmosphere of fantastical painterly worlds, the emotion behind his art remains as palpable as ever. Now hinting at more poignant moments and communicating concepts that move beyond the generational gap, Wu Qiong’s art moves firmly from the nostalgic world of children into the ever-changing, ever-reflective present reality.

Important Collections

Musée des Beaux-Arts de Tours (Museum of Fine Arts of Tours), Tours, France

(Sculpture) Asian Art Museum of Cuba (Prints)

Managing Director and Founder of MediaCorp Raintree Pictures (Singapore), Daniel Yun (Oil Painting)

MediaCorp artiste Mark Lee, Singapore (Sculpture, Oil Painting, Prints)

Celebrity Stylist, Addy Lee, Singapore (Sculpture, Oil Painting, Prints)

Founder of Upfront Models modeling agency, Watson Tan (Sculpture, Oil Painting)

ACP Magazines (Cleo, Women’s Weekly) Chief Fashion Editor, Sally Teo (Oil Painting)

Television host and MediaCorp artiste, Quan Yi Fong (Oil Painting)

Television host and MediaCorp artiste, Ben Yeo (Oil Painting)

Malaysia Singapore embassy in Malaysia (Oil Painting)

Exhibitions

Exhibitions

Selected exhibitions

2020

Inside the Creative Space, Virtual Solo Exhibition, Ode To Art, Singapore

2019

Asia Contemporary Art Show, Conrad Hong Kong

2017

Partial Archive, Yell Space, Shanghai, China

2015

Here and Now by Wu Qiong, Ode To Art Gallery, Singapore

Lanjing Arts Center

Tokyo International Mini Print Triennial, Tokyo, Japan

2014

Art Stage 2014, Ode to Art Gallery, Singapore

Reproduce - Artists Create, Artists’ Gallery, 798 Art Zone, Beijing

0614, Beijing International Cultural Exchange Private Limited, China

Waiting – Wu Qiong, Fei Ni Qi Art Center, 798 Art Zone, Beijing

2013

Art Hong Kong, Ode to Art Gallery, Singapore

Reproduction1: Silence, All Art Contemporary Art Center, Building No. 2, 798 Art Zone, Beijing

Ding Ding & Little Friends, c-space, The Gallery

Art Stage 2013, Ode to Art Gallery, Singapore

2012

Essence of Performing, Sunjin Gallery, Singapore

Art Stage Singapore, Ode to Art Gallery, Singapore

2011

Asian Art Museum of Cuba, Collection Show, Contemporary Printmaking, Beijing Hexagon Contemporary Art Exchange Center

Affordable Art Fair with Sunjin Gallery, Singapore

Explosion of Colors, Art Front Collective, Singapore

2010

Hidden Rules, Shiyu Space, 798 Art Zone, Beijing

Width 2 Contemporary Art Exhibition, Museum of Contemporary Art, Beijing

Crossover – International Exhibition 2010 (Singapore Venue), Sunshine International Museum, Beijing

Art Expo Malaysia 2010 with Sunjin Gallery Singapore, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Affordable Art Fair, Sunjin Gallery, Singapore

2009

Feeling – Shandong, Zuoyu Contemporary Museum, Shandong

My Friends, My Place, Hong Wan Arts Center, Beijing, Songzhuang

Chinese Contemporary Art Exhibition in France, “Recent History,” Musée des Beaux-Arts de Tours (Museum of Fine Arts of Tours), Tours, France

Shanghai Contemporary 2009, Shanghai, China

Realm – Heart, 798 Art Zone, Beijing

2008

Hear Us Out, Sunjin Gallery, Singapore

Bridge Art Fair, New York 2008, Galerie Kashya Hildebrand, Switzerland

Art Cologne 2008, Galerie Kashya Hildebrand, Switzerland

China International Gallery Exposition 2008, Beijing, Galerie Kashya Hildebrand, Switzerland

11th Beijing International Art Exposition, Sunjin Galleries, Singapore

From Mao to Now, Sydney Olympic Park Authority, Australia, with Sunjin Gallery, Singapore

The Sunshine Invitation of International Art Annual Exhibition, Sunshine International Museum – Beijing

Art Singapore 2008, The Contemporary Asian Art Fair, Sunjin Galleries, Singapore

2007

Born in the 80’s, Sunjin Gallery, Singapore

ArtSingapore 2007, The Contemporary Asian Art Fair, Suntec City, Sunjin Galleries, Singapore

Emerging Talent – Five Artists for the Future, Sunjin Galleries, Singapore

Art Miami 2007, Galerie Kashya Hildebrand, Switzerland

2006

Painting Showcase at POP@Central, Bras Basah, Singapore

Senses of Place, NAFA Campus 1, Singapore

Visual Desire Group Contemporary Art Exhibition, Singapore

100% Made in Singapore – Art Seasons Gallery, Singapore

ArtSingapore 2006, The Contemporary Asian Art Fair, Suntec City, Sunjin Galleries, Singapore

Crazily Vertiginous Chinese Contemporary Art Exhibition, Sunjin Galleries, Singapore

Form and Sensitivity Group Exhibition, Sunjin Galleries, Singapore

WTP Windows to the Past with Sunjin Galleries, Singapore

2005

MAAP Multi Element Visual Performance, Singapore Art Museum

2020

Inside the Creative Space, Virtual Solo Exhibition, Ode To Art, Singapore

2019

Asia Contemporary Art Show, Conrad Hong Kong

2017

Partial Archive, Yell Space, Shanghai, China

2015

Here and Now by Wu Qiong, Ode To Art Gallery, Singapore

Lanjing Arts Center

Tokyo International Mini Print Triennial, Tokyo, Japan

2014

Art Stage 2014, Ode to Art Gallery, Singapore

Reproduce - Artists Create, Artists’ Gallery, 798 Art Zone, Beijing

0614, Beijing International Cultural Exchange Private Limited, China

Waiting – Wu Qiong, Fei Ni Qi Art Center, 798 Art Zone, Beijing

2013

Art Hong Kong, Ode to Art Gallery, Singapore

Reproduction1: Silence, All Art Contemporary Art Center, Building No. 2, 798 Art Zone, Beijing

Ding Ding & Little Friends, c-space, The Gallery

Art Stage 2013, Ode to Art Gallery, Singapore

2012

Essence of Performing, Sunjin Gallery, Singapore

Art Stage Singapore, Ode to Art Gallery, Singapore

2011

Asian Art Museum of Cuba, Collection Show, Contemporary Printmaking, Beijing Hexagon Contemporary Art Exchange Center

Affordable Art Fair with Sunjin Gallery, Singapore

Explosion of Colors, Art Front Collective, Singapore

2010

Hidden Rules, Shiyu Space, 798 Art Zone, Beijing

Width 2 Contemporary Art Exhibition, Museum of Contemporary Art, Beijing

Crossover – International Exhibition 2010 (Singapore Venue), Sunshine International Museum, Beijing

Art Expo Malaysia 2010 with Sunjin Gallery Singapore, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Affordable Art Fair, Sunjin Gallery, Singapore

2009

Feeling – Shandong, Zuoyu Contemporary Museum, Shandong

My Friends, My Place, Hong Wan Arts Center, Beijing, Songzhuang

Chinese Contemporary Art Exhibition in France, “Recent History,” Musée des Beaux-Arts de Tours (Museum of Fine Arts of Tours), Tours, France

Shanghai Contemporary 2009, Shanghai, China

Realm – Heart, 798 Art Zone, Beijing

2008

Hear Us Out, Sunjin Gallery, Singapore

Bridge Art Fair, New York 2008, Galerie Kashya Hildebrand, Switzerland

Art Cologne 2008, Galerie Kashya Hildebrand, Switzerland

China International Gallery Exposition 2008, Beijing, Galerie Kashya Hildebrand, Switzerland

11th Beijing International Art Exposition, Sunjin Galleries, Singapore

From Mao to Now, Sydney Olympic Park Authority, Australia, with Sunjin Gallery, Singapore

The Sunshine Invitation of International Art Annual Exhibition, Sunshine International Museum – Beijing

Art Singapore 2008, The Contemporary Asian Art Fair, Sunjin Galleries, Singapore

2007

Born in the 80’s, Sunjin Gallery, Singapore

ArtSingapore 2007, The Contemporary Asian Art Fair, Suntec City, Sunjin Galleries, Singapore

Emerging Talent – Five Artists for the Future, Sunjin Galleries, Singapore

Art Miami 2007, Galerie Kashya Hildebrand, Switzerland

2006

Painting Showcase at POP@Central, Bras Basah, Singapore

Senses of Place, NAFA Campus 1, Singapore

Visual Desire Group Contemporary Art Exhibition, Singapore

100% Made in Singapore – Art Seasons Gallery, Singapore

ArtSingapore 2006, The Contemporary Asian Art Fair, Suntec City, Sunjin Galleries, Singapore

Crazily Vertiginous Chinese Contemporary Art Exhibition, Sunjin Galleries, Singapore

Form and Sensitivity Group Exhibition, Sunjin Galleries, Singapore

WTP Windows to the Past with Sunjin Galleries, Singapore

2005

MAAP Multi Element Visual Performance, Singapore Art Museum

Critique

Critique

Wu Qiong’s “Chinese Children” by Daozi

Wu Qiong’s work mainly consists of three series: Born in the 1980s, Marching Forth and Made in China.

From ancient Song dynasty paintings "Street Vendor" and "Children Playing" to Feng Zikai’s comics and Zhang Leping’s Sanmao in more recent years, children have been an important subject matter for many artists. These works depict the various situations and encounters of children, highlight their naïveté and loveliness and even the helplessness and tragedy of children living in lower tiers of society. Through these representations, the artists express their longing for the purity of being a child, whilst revealing the darker side of society. Since the 1980s, as art and culture bloomed, more works with the theme of children emerged in contemporary Chinese art such as Zhang Xiaogang’s Blood Family series, Tang Zhigang’s Children’s Conference and Chinese Fable series, Cui Xiuwen’s Angel series, and so on. Within these works, there has been a shift in focus from depicting children directly, to using children thematically as a subject matter. The artists no longer simply portray children in real life, but have placed them in imaginative spaces. Through the theme of children, social issues are revealed, the sentiments of love and concern are expressed, an individual’s condition of existence in the contemporary society is conveyed. The subject matter transcends children per se, and instead addresses societal concerns and life experiences of artists.

This transition in the new era allowed for a freer representation of children. Children began to appear in quasi-realistic situations, with changing appearances and expressions that were increasing rich and diverse. Their bodies were still that of children, but their behaviour was no longer naïve and childish. They seemed to have taken on the sensitivity of adults with mature emotions. The depicted children bid farewell to their years of innocence, as there seemed to be a distancing from their real-life counterparts. They are objectified under the artists’ brush. Such are the characteristics of the children in Wu Qiong’s work. He sets children in fictional scenarios and, through the appropriation of images of children, makes references to adult experiences, social issues or even historical consciousness. As the artist claims, if our paintings could be represented with more vivid scenarios and narration, allowing the audience to perceive a certain “surrealist” quality, artwork would be more sensational and discrete.

Childhood Memories

In Wu Qiong’s Eighties series, the children are whipping tops, having snowball fights, rolling iron rings, kicking shuttlecocks and playing hopscotch. Like it's title, these are childhood memories of those born in the 1980s and memories of childhood in old Beijing.

The children in these images have their eyes closed and heads lifted towards the airy blue sky and cotton clouds surrounding them, as if playing in a dream. Illusion and gracefulness are the main impression conveyed in this work, a feeling extricated from our childhood—the joy of carefree playing, the happiness of not having any responsibility.

Milan Kundera discusses the question of lightness and weight in the Unbearable Lightness of Being, “The weightier our responsibilities are, the closer our lives are to the earth, it is more realistic. On the contrary, when responsibility is absent, people become lighter than the air, they float, and are distanced from the earth and their lives on earth. People would become pseudo-beings, and their movement would also become free and meaningless.” The so-called weight of being refers to the burdens and oppression of life. On the journey of life, as one matures, one seeks out desires, ideals, responsibilities and duties, with which comes various limitations and consequences, such as pain, tribulation, burden and oppression. In fact, we only live once and what is irreversibly lost is, in Kundera’s view, the lightness of being—the true condition of being. And the lightness of being originates in its meaninglessness.

Life is light, unbearably light. On life’s journey, we have always been “children,” we have never left our vague childhood, but we are still roaming in a void. Yet, although we are well aware of it, we still can’t abandon certain heavy burdens, which can be as significant as fame and benefits and as insignificant as the necessities of life. For adults, the lightness of being can be acknowledged but cannot be experienced—as we get to know the lightness better, we have already begun to walk away from it.

Made in China series

With their eyes still shut and heads lifted, the children look perplexed. They are sloppily wearing official dress, holding glazed fruit sticks, squatting on the floor holding hands with a bride, or hanging out with friends. Looking at these scenes is like a glimpse into everyday Chinese life -the quest for survival, fame, for the next generation, for friends to drink and chat with.

The content in one’s life is mostly regulated by society, a result of cultural production. Children are taught mostly through regulation and are constantly indoctrinated with adult world ideals and expectations influenced by current cultural and social conditions. For example, they must study, work in offices, have a son to continue their lineage; as well as follow principles of loyalty, filial piety, propriety and such.

Living within the confinements of such a moral system, one’s life is predestined from life to death; it becomes unnecessary to consider individual will. In this society, we are just children lavished with excessive attention. Although, if we reflect on these societal values in various situations, they seem rather absurd and laughable. A glazed fruit stick, the official costume, an old companion, a few friends to drink and chat with, this is what have been safekeeping, protecting and striving for—a laughable yet helpless situation.

Marching Forth series

This series portrays three groups of children with similar expressions and behavior. From their attire, we can categorize them into different eras: the Republican period, the Cultural Revolution period and the 1980s. Here we witness different education models - both familial and societal - for children in various periods. The tradition in ancient China was to educate one's children. In the “Rites of Qu” or Book of Rites, household rules included toddlers being taught basic concepts of how to behave as men and women. Content of education had to be centered on respecting the elders, their community and other behavioural rules, as well as mathematics, geography, how to read calendars and basic knowledge of everyday life. Once the children entered school, which was usually after ten years of age, besides learning the classics, the children were taught Neo-Confucianism ideals and the value of learning. In teaching children, one was meant to follow the Book of Rites and implement rules regulating behavior. The focus of education was on cultivation of character, whereas acquiring knowledge was secondary and a continuous process.

After the Qing government established its examination system, there were changes in the Neo-Confucian education of children. As becoming a literati turned into an opportunity to move up the social ladder, Ming and Qing dynasty scholars had to readjust the goals and content of childhood education and developed a new system of pedagogy and methodology. During the Ming and Qing dynasties, many supplementary materials were made for early education. The editors and authors uniformly expressed (in the prefaces of their writings) the need and responsibility of transitioning private education for one’s children into a type of public duty. Children were gradually breaking away from private family teaching, and becoming the subject of concern outside of the family unit (in public and society) or system (school and education systems), which allowed children to be easily influenced by changes in society and become part of it.

There is a Chinese expression stating children were educated for “various ancestors,” and later it was also for the purpose of “social benefits” and “prosperity of the nation.” In recent years, childhood education became a public project. The existence of children seems to serve a purpose beyond the children themselves. In other words, within the framework of this era, the meaning of every individual’s life is beyond him or herself. As such, children have lost their individuality and exist as members of a collective that are “marching forth in unison” with those around them. Yet, for adults, aren’t they also confronted with the same issues?

Rectifying the 1980's Generation

Overall, children have not always been a subject of choice for Wu Qiong and the appropriation of children to scrutinize our conditions of life isn’t necessarily his usual theme. In his 2006 graduation project, we see a depressed young man. "Moment" was a series of sketches of sad expressions, convoluted facial features and inconsistent expressions that belied oppression and sadness. In "Untitled" and "Cry," such oppression is displayed more apparently. "Puzzled C Major" and "Poet’s Talk on Dreams" of the same period demonstrate the helplessness and compromise in post-hysteria. If complaints and anger did not change anything, then why take on a playful angle to banter, satirize and reveal? The artist takes the so-called “culture,” “value” and “tradition” that binds him and places this in front of an audience, allowing everyone to reflect while laughing at them. In "Eighty or Eighty," Wu Qiong wrote, “I am using playful images to express happiness, sadness, alarm and self-parody.” The artist expressed these ideals through the images of children.

As a young artist from the 1980s, scrutiny and judgment was inevitable. His new work, "Born after 1980," is a manifestation of that situation: a small child stands alone on a reef and behind him is blue ocean and sky. His body is pattered by the waves and the child looks out and shivers. Using the artist’s own words, “I am using my unique artistic language to respond to the various attacks on the 1980s generation from society, by contrasting it with the ocean to highlight my insignificance. But the child still stands out and welcomes the rush of the ocean. Thus, I hope the audience would learn about the spirit of the 1980s generation.”

To a certain degree, Wu Qiong’s paintings have rectified a common criticism—the tendency to categorize art groups according to their biological age and neglecting the most important element of ideas in the contemporaneity of art. The common criticism of the ‘80s generation is their shared and habitual characteristics. They are portrayed as a generation that grew up in an urban setting; thus, they refer to cities as the center of their lives and their observations are based on books, films, the media and their own circles of friends. They talk about fashion, architecture, politics and the tabloids, and they seem to maintain a hedonistic lifestyle. They resemble a class in exile, who not only lack the instinct to live in a carefree fashion as the ’90s generation does, but also do not wish to carry any sense of collective responsibility like their predecessors. Their innate sense of oppression and persistent pursuit of freedom is precisely the destiny of this generation. These claims seem to be quite a generalization of this generation, but they are just as speculative. However, it should be noted that outstanding ideas and art are without borders and can transcend generations, or even time. Since Wu Qiong returned from his studies in Singapore, in addition to his clear international perspective, he is, more importantly, constantly defining his position and injecting it into the undercurrents of this era.

Wu Qiong’s work mainly consists of three series: Born in the 1980s, Marching Forth and Made in China.

From ancient Song dynasty paintings "Street Vendor" and "Children Playing" to Feng Zikai’s comics and Zhang Leping’s Sanmao in more recent years, children have been an important subject matter for many artists. These works depict the various situations and encounters of children, highlight their naïveté and loveliness and even the helplessness and tragedy of children living in lower tiers of society. Through these representations, the artists express their longing for the purity of being a child, whilst revealing the darker side of society. Since the 1980s, as art and culture bloomed, more works with the theme of children emerged in contemporary Chinese art such as Zhang Xiaogang’s Blood Family series, Tang Zhigang’s Children’s Conference and Chinese Fable series, Cui Xiuwen’s Angel series, and so on. Within these works, there has been a shift in focus from depicting children directly, to using children thematically as a subject matter. The artists no longer simply portray children in real life, but have placed them in imaginative spaces. Through the theme of children, social issues are revealed, the sentiments of love and concern are expressed, an individual’s condition of existence in the contemporary society is conveyed. The subject matter transcends children per se, and instead addresses societal concerns and life experiences of artists.

This transition in the new era allowed for a freer representation of children. Children began to appear in quasi-realistic situations, with changing appearances and expressions that were increasing rich and diverse. Their bodies were still that of children, but their behaviour was no longer naïve and childish. They seemed to have taken on the sensitivity of adults with mature emotions. The depicted children bid farewell to their years of innocence, as there seemed to be a distancing from their real-life counterparts. They are objectified under the artists’ brush. Such are the characteristics of the children in Wu Qiong’s work. He sets children in fictional scenarios and, through the appropriation of images of children, makes references to adult experiences, social issues or even historical consciousness. As the artist claims, if our paintings could be represented with more vivid scenarios and narration, allowing the audience to perceive a certain “surrealist” quality, artwork would be more sensational and discrete.

Childhood Memories

In Wu Qiong’s Eighties series, the children are whipping tops, having snowball fights, rolling iron rings, kicking shuttlecocks and playing hopscotch. Like it's title, these are childhood memories of those born in the 1980s and memories of childhood in old Beijing.

The children in these images have their eyes closed and heads lifted towards the airy blue sky and cotton clouds surrounding them, as if playing in a dream. Illusion and gracefulness are the main impression conveyed in this work, a feeling extricated from our childhood—the joy of carefree playing, the happiness of not having any responsibility.

Milan Kundera discusses the question of lightness and weight in the Unbearable Lightness of Being, “The weightier our responsibilities are, the closer our lives are to the earth, it is more realistic. On the contrary, when responsibility is absent, people become lighter than the air, they float, and are distanced from the earth and their lives on earth. People would become pseudo-beings, and their movement would also become free and meaningless.” The so-called weight of being refers to the burdens and oppression of life. On the journey of life, as one matures, one seeks out desires, ideals, responsibilities and duties, with which comes various limitations and consequences, such as pain, tribulation, burden and oppression. In fact, we only live once and what is irreversibly lost is, in Kundera’s view, the lightness of being—the true condition of being. And the lightness of being originates in its meaninglessness.

Life is light, unbearably light. On life’s journey, we have always been “children,” we have never left our vague childhood, but we are still roaming in a void. Yet, although we are well aware of it, we still can’t abandon certain heavy burdens, which can be as significant as fame and benefits and as insignificant as the necessities of life. For adults, the lightness of being can be acknowledged but cannot be experienced—as we get to know the lightness better, we have already begun to walk away from it.

Made in China series

With their eyes still shut and heads lifted, the children look perplexed. They are sloppily wearing official dress, holding glazed fruit sticks, squatting on the floor holding hands with a bride, or hanging out with friends. Looking at these scenes is like a glimpse into everyday Chinese life -the quest for survival, fame, for the next generation, for friends to drink and chat with.

The content in one’s life is mostly regulated by society, a result of cultural production. Children are taught mostly through regulation and are constantly indoctrinated with adult world ideals and expectations influenced by current cultural and social conditions. For example, they must study, work in offices, have a son to continue their lineage; as well as follow principles of loyalty, filial piety, propriety and such.

Living within the confinements of such a moral system, one’s life is predestined from life to death; it becomes unnecessary to consider individual will. In this society, we are just children lavished with excessive attention. Although, if we reflect on these societal values in various situations, they seem rather absurd and laughable. A glazed fruit stick, the official costume, an old companion, a few friends to drink and chat with, this is what have been safekeeping, protecting and striving for—a laughable yet helpless situation.

Marching Forth series

This series portrays three groups of children with similar expressions and behavior. From their attire, we can categorize them into different eras: the Republican period, the Cultural Revolution period and the 1980s. Here we witness different education models - both familial and societal - for children in various periods. The tradition in ancient China was to educate one's children. In the “Rites of Qu” or Book of Rites, household rules included toddlers being taught basic concepts of how to behave as men and women. Content of education had to be centered on respecting the elders, their community and other behavioural rules, as well as mathematics, geography, how to read calendars and basic knowledge of everyday life. Once the children entered school, which was usually after ten years of age, besides learning the classics, the children were taught Neo-Confucianism ideals and the value of learning. In teaching children, one was meant to follow the Book of Rites and implement rules regulating behavior. The focus of education was on cultivation of character, whereas acquiring knowledge was secondary and a continuous process.

After the Qing government established its examination system, there were changes in the Neo-Confucian education of children. As becoming a literati turned into an opportunity to move up the social ladder, Ming and Qing dynasty scholars had to readjust the goals and content of childhood education and developed a new system of pedagogy and methodology. During the Ming and Qing dynasties, many supplementary materials were made for early education. The editors and authors uniformly expressed (in the prefaces of their writings) the need and responsibility of transitioning private education for one’s children into a type of public duty. Children were gradually breaking away from private family teaching, and becoming the subject of concern outside of the family unit (in public and society) or system (school and education systems), which allowed children to be easily influenced by changes in society and become part of it.

There is a Chinese expression stating children were educated for “various ancestors,” and later it was also for the purpose of “social benefits” and “prosperity of the nation.” In recent years, childhood education became a public project. The existence of children seems to serve a purpose beyond the children themselves. In other words, within the framework of this era, the meaning of every individual’s life is beyond him or herself. As such, children have lost their individuality and exist as members of a collective that are “marching forth in unison” with those around them. Yet, for adults, aren’t they also confronted with the same issues?

Rectifying the 1980's Generation

Overall, children have not always been a subject of choice for Wu Qiong and the appropriation of children to scrutinize our conditions of life isn’t necessarily his usual theme. In his 2006 graduation project, we see a depressed young man. "Moment" was a series of sketches of sad expressions, convoluted facial features and inconsistent expressions that belied oppression and sadness. In "Untitled" and "Cry," such oppression is displayed more apparently. "Puzzled C Major" and "Poet’s Talk on Dreams" of the same period demonstrate the helplessness and compromise in post-hysteria. If complaints and anger did not change anything, then why take on a playful angle to banter, satirize and reveal? The artist takes the so-called “culture,” “value” and “tradition” that binds him and places this in front of an audience, allowing everyone to reflect while laughing at them. In "Eighty or Eighty," Wu Qiong wrote, “I am using playful images to express happiness, sadness, alarm and self-parody.” The artist expressed these ideals through the images of children.

As a young artist from the 1980s, scrutiny and judgment was inevitable. His new work, "Born after 1980," is a manifestation of that situation: a small child stands alone on a reef and behind him is blue ocean and sky. His body is pattered by the waves and the child looks out and shivers. Using the artist’s own words, “I am using my unique artistic language to respond to the various attacks on the 1980s generation from society, by contrasting it with the ocean to highlight my insignificance. But the child still stands out and welcomes the rush of the ocean. Thus, I hope the audience would learn about the spirit of the 1980s generation.”

To a certain degree, Wu Qiong’s paintings have rectified a common criticism—the tendency to categorize art groups according to their biological age and neglecting the most important element of ideas in the contemporaneity of art. The common criticism of the ‘80s generation is their shared and habitual characteristics. They are portrayed as a generation that grew up in an urban setting; thus, they refer to cities as the center of their lives and their observations are based on books, films, the media and their own circles of friends. They talk about fashion, architecture, politics and the tabloids, and they seem to maintain a hedonistic lifestyle. They resemble a class in exile, who not only lack the instinct to live in a carefree fashion as the ’90s generation does, but also do not wish to carry any sense of collective responsibility like their predecessors. Their innate sense of oppression and persistent pursuit of freedom is precisely the destiny of this generation. These claims seem to be quite a generalization of this generation, but they are just as speculative. However, it should be noted that outstanding ideas and art are without borders and can transcend generations, or even time. Since Wu Qiong returned from his studies in Singapore, in addition to his clear international perspective, he is, more importantly, constantly defining his position and injecting it into the undercurrents of this era.

Stay connected.

Sign up to our newsletter for updates on new arrivals and exhibitions