Gusmen Heryadi was born in 1974 in Pariaman, West Sumatra, Indonesia. Having graduated from the Indonesian Institute of the Arts (ISI) in 2005, he now works as an illustrator at Tabloid Altternatif Pualiggoubat Mentawai in his hometown.

Gusmen has been actively exhibiting his work over the past two decades. He won an award in Indonesia for Space and Image, that is exhibited at Ciputra World Marketing Gallery. He has also been a finalist of both the Philip Morris and Indofood Art Awards (2000 and 2002), and has been honoured with a Special Appreciation w for the Jakarta Art Award in 2006.

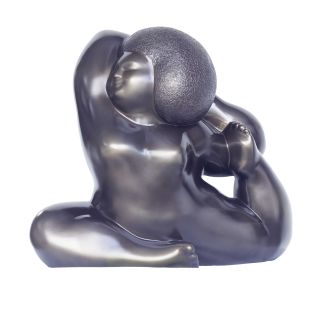

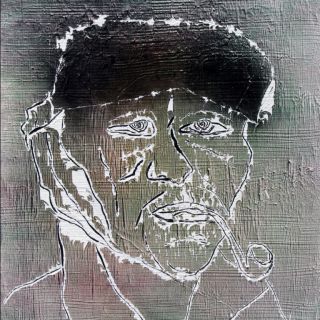

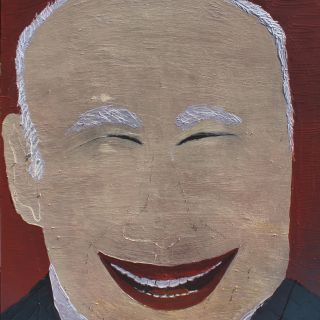

The objects featured in his paintings are often metaphors of his feelings and inner debates about the issues of culture and tradition in a modern society. Most of his works are products of his dreams, his responses to life, and his philosophical views. These philosophical and critical thoughts are the result of cultural development and family habits, as well as influences from the breadth of his artistic life and pursuits.

Viewing 2 works by Gusmen

Sort

Biography

Biography

Gusmen Heryadi was born in 1974 in Pariaman, West Sumatra, Indonesia. Having graduated from the Indonesian Institute of the Arts (ISI) in 2005, he now works as an illustrator at Tabloid Altternatif Pualiggoubat Mentawai in his hometown. Gusmen has been actively exhibiting his work over the past two decades. He won an award in Indonesia for Space and Image, that is exhibited at Ciputra World Marketing Gallery. He has also been a finalist of both the Philip Morris and Indofood Art Awards (2000 and 2002), and has been honoured with a Special Appreciation at the Jakarta Art Awards in 2006.

The objects featured in his paintings are often metaphors of his feelings and inner debates about the issues of culture and tradition in a modern society. Most of his works are products of his dreams, his responses to life, and his philosophical views. These philosophical and critical thoughts are the result of cultural development and family habits, as well as influences from the breadth of his artistic life and pursuits.

Awards

2006 Special Appreciation of Jakarta Art Award, Indonesia

2002 Finalist of Indofood Art Award, Indonesia

2000 Finalist of Philip Morris Art Award, Indonesia 1998 Finalist of Philip Morris Art Award, Indonesia

1997 The Best Acrylic Painting, ISI Yogyakarta, Indonesia

1996 The Best Watercolor Painting, ISI Yogyakarta

The objects featured in his paintings are often metaphors of his feelings and inner debates about the issues of culture and tradition in a modern society. Most of his works are products of his dreams, his responses to life, and his philosophical views. These philosophical and critical thoughts are the result of cultural development and family habits, as well as influences from the breadth of his artistic life and pursuits.

Awards

2006 Special Appreciation of Jakarta Art Award, Indonesia

2002 Finalist of Indofood Art Award, Indonesia

2000 Finalist of Philip Morris Art Award, Indonesia 1998 Finalist of Philip Morris Art Award, Indonesia

1997 The Best Acrylic Painting, ISI Yogyakarta, Indonesia

1996 The Best Watercolor Painting, ISI Yogyakarta

Exhibitions

Exhibitions

2010

Korea International Art Fair, Coex, Seoul, South Korea

Bakaba, with Sakato Group, Jogja National Museum, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

2009

Bazaar Art Fair, Ritz Carlton - Pacific Place, Jakarta, Indonesia

In Rainbow, Esa Sampoerna Art House, Surabaya, Indonesia

C-Art Show, Grand Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia

2008

Manifesto, Galeri National Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia

A New Force of South East Asia: Group Exhibitions of Indonesian Contemporary Artists, Asia Art Centre, Beijing, China

2007

Inspiring Indonesian Contemporary Art, Organized by Media Visual Art, Shanghai Art Fair, China

2006

Kisi-Kisi Jakarta, Jakarta Art Award, Jakarta, Indonesia

Bazart, Benteng Vredeburg Museum, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

2004

Menimbang Tradisi, Sanggar Sakato, National Gallery, Jakarta, Indonesia

Korea International Art Fair, Coex, Seoul, South Korea

Bakaba, with Sakato Group, Jogja National Museum, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

2009

Bazaar Art Fair, Ritz Carlton - Pacific Place, Jakarta, Indonesia

In Rainbow, Esa Sampoerna Art House, Surabaya, Indonesia

C-Art Show, Grand Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia

2008

Manifesto, Galeri National Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia

A New Force of South East Asia: Group Exhibitions of Indonesian Contemporary Artists, Asia Art Centre, Beijing, China

2007

Inspiring Indonesian Contemporary Art, Organized by Media Visual Art, Shanghai Art Fair, China

2006

Kisi-Kisi Jakarta, Jakarta Art Award, Jakarta, Indonesia

Bazart, Benteng Vredeburg Museum, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

2004

Menimbang Tradisi, Sanggar Sakato, National Gallery, Jakarta, Indonesia

Critique

Critique

A Matter of Gusmen's Guests

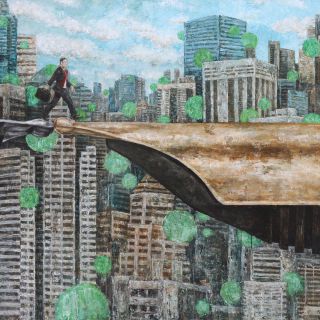

Gusmen has been titling his works "Tamu" ("Guest") for a long time. However, he never determined to present this series of "guests paintings" as a unified whole which would be established into a solo exhibition. All this time, his works entitled "Guest" have been included in other exhibitions he participated in. Out of the numerous works he has created, the "Guests" series has a certain appeal of its own that can elucidate the main points of Gusmen's artistic concept. Therefore, in this year's solo exhibition, Gusmen Heriadi finally presented the title Guests. It is a simple word that corresponds with "traveler", "newcomer" or "visitor." Gusmen and I do not use any of those three words because "guest" induces an enigma or imposes a certain mystery. It has more emotive meaning, eliciting emotions as compared to the other corresponding words that are more "generic." Hence, in addition to being symbolic, the word "guest" also carries a plurality of meanings as well as conveying overlapping issues. It is an umbrella for the various things he uses as materials to expand the discussion. For Gusmen, Guests is also a matter of "arrival" and "departure." It is about someone who "comes" and "goes," invited or otherwise.

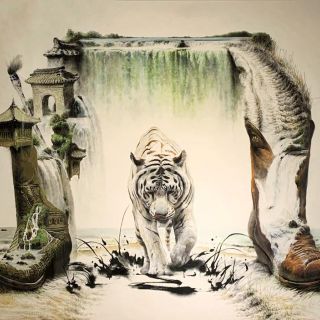

Gusmen presents many human figures as the main subject of all his works. The figures are depicted in different poses such as falling from the sky or rolling from behind the trees. In Guest #8 (2008), the naked figures look as if they just arrived (or could be about to go) from or into an alley formed by a wide gap between the trees. The trees are brownish black, as if burned dry. The alley curves into a dark turn. Two white lines at the end of the turn build an illusion in the shape of a small door. The presence of a blue pond does not just add an accent to the painting, but also strengthens the impression of mystery. All of these elements successfully stimulate a layered process of meaning. Guest #8 adopts a naturalist style of painting. Even so, it is not the feeling of beauty or admiration being perceived, but rather an allure to enter the gloomy atmosphere that would negate our emotions towards nature.

In this series, Gusmen also utilizes a background that gives a panoramic impression - a vast desert with a faint horizon line depicted. In Guest #2 (2007), there is a door on the horizon line that runs diagonally. This door creates very strong direction about the origin of an arrival and departure gate for the figures - like a final exit that gives a men a last chance to make a decision. In some cases, such an atmosphere is reminiscent of the waiting room in a terminal at the airport - a worrisome place, because one never knows if we will reach the destination we are headed to. We, in that situation, can just surrender. In Gusmen's painting, concepts of a terminal or airport are replaced with dense forests, vast savannahs, corners of rooms and beaches.

As we see in Guest #9, the figures are suggested to be "floating" above the beach that divides the land and the ocean. Aside from this, he adds a "second background" with three lines that build the appearance of a corner of a room and its door. This layered background gives the illusion of both a world within and an outside world, or as voiced by the late art critic Sudarmadji - "intrinsic" and "extrinsic." These two factors could be used as indicators to help the artist comprehend and assess the "world" around him. We can postpone the in-depth analysis of these two factors to later discussions. However, with this provision, we can generally evaluate that the use of background in Gusmen's paintings invites a layered meaning. This also means that Gusmen pays attention to the background as something important to be studied.

Almost all the figures in his paintings are seen as a clustered mess. But in one or two paintings they seem to form a pattern or specific configuration. In the painting Guest #9 (2008), for example, the configuration is formed into "prayer beads," while in another work we find only one figure. Up to this point, the significance of fragmentary and patterned figures could deviate the discourse of disorder and order. Meanwhile, when the figures are examined one by one, we find that each figure is given a cushion or platform to rest upon and some of them form a comfortable couch. This causes each figure to not be stepping on the earth. These figures and the positioning of them thus develop the idea in our minds of the arrival and departure of "guests."

If Gusmen represents the figure of a post-colonial artist, then perhaps his works are built upon local interest and deal with the questions of identity, history and globalization. Nevertheless, as with several painters in his generation, Gusmen does not urge his art to be a "political statement," nor does he assign art as an instrument for social change as most artists did in the late 1990s. Political arts and social criticism have a strong influence on young artists' practice of art, however Gusmen does not appear to be in this category. His style is sublime rather than provocative.

Amidst the gloom and obscurity of the Indonesian contemporary art scene until the mid-2000s, the debate about contemporary art involved two remaining views which valid arguments had not proven. The first was the assumption that Indonesian contemporary art was identical to arts that had a critical dimension - criticisms directed against the political world and the power of the state. Art in these terms were also identical to the artists' defence against social reality. Works of art by artists were used to not only narrate matters of social pathology but also with a certain awareness that tended to be applied to defend and define the agenda of change for society. Thus, "Indonesian contemporary art", recognized by a handful of art observers, in itself carried the "morality."

Second was the view which agreed that Indonesian contemporary art was identical to the "market." Artists were confronted by the fact that their artworks were nothing more than commodities of the market. This reality potentially restricted the artistic space of artists. Despite this, paradoxically, this fact was discreetly celebrated as well. For those who favored the market, the first argument was viewed to be against reality and they questioned the fundamentals of the assessment of the relationship between the practice of art and morality. Such criticism is then developed by raising a new question: is the morality in this context actually "market morality," which is aligned with ethics and market demand?

Gusmen, who graduated from ISI Yogyakarta in 2005, began his career in the middle of this situation. He was aware that the position of an artist was not as secure as he imagined it to be and realized that the reality he faced was uncertain. He did not exactly favor the "critical arts camp." On the other hand, he did not necessarily support the "commodity arts camp" either. He tried to escape this tension and eventually chose to concentrate on aesthetic explorations. He wanted to explore the potential plane (canvas), and arrange the strength of his painting's character while staying receptive to "influences" that he deemed as worthy to be developed and adapted to his artistic instincts.

Similar to his friends in the Sakato Arts Community and Genta, Gusmen is an artist who chose a different path out of the two previously fixed choices. These artists (traveling artists from West Sumatra) aim to re-establish the "universality of art" but with a belief that is not ultimate nor absolute - just like Western modernist credos. Gusmen believes that it is not his responsibility as an individual to think that art can save the world, though art can actually sustain humanity. In turn, art will reveal identity, reflect culture and form a civilization. That is why he and dozens of other artists in that community welcome any effort that aims to promote artistic discoveries for the development of Indonesian art. To some extent, this attitude managed to minimize the uncertainties of their social status in the field of art. It also frees the artists from a number of determinations and restrictions set by the world around them.

As interpreted by other young artists, in the midst of such apprehension, the term contemporary art is not something that is certain and therefore should be relied upon. Gusmen does not trap himself in that kind of "battle of discourse." He does not compose a strategy let alone formulate a method to be accepted in the "field of Indonesian contemporary arts". For him, such a choice will only confine the artists within unnecessary terminology.

There are other more important tasks young artists should carry out, he feels. Gusmen actively participates in various art exhibitions and continuously promotes different artistic creations. He claims that this is the only way an artist can better understand and deepen his works.

Existentialism

Every young artist who started his career in the art world has at one time or another contemplated his true identity. In the process, he searches for the "differences" and "similarities" between himself and other artists. The results often are a dead end. However, many young artists managed to emerge from this deep reflection and "find themselves."

The discovery of identity is still a process. What is typical about this process is there will always be a personification (embodiment) of an artist through a number of forms in his works. It is not uncommon that an artwork is a personification of the artist. Matters of the "self," "individual constructions" and "the search for identity" are reflected. However, not everything can be deciphered clearly and explicitly which is what makes art interesting. One is saying something that cannot be said. The artist depicts emotions and ideals that are difficult to express normally.

Art is a hiding place from "the self" and presents an artist's "private atmosphere" for others to view. Every artist has a lot of ways to present this "atmosphere." What stands out in Gusmen's works is the strong ability to deliver a vast, grim and quiet "atmosphere" which immediately persuades us to question the "fate" of man as a "guest" in the world. As mentioned, the "background" in Gusmen's paintings holds the same "weight of meaning" as the human figures. Both are equally important because their meanings correlate with each other. This background is not a mere "background to decorate a painting" but possesses deeper meaning.

In conclusion, Gusmen's series of Guests immediately causes us to reevaluate why we come and go, why we must "visit" this world? At this point, we turn to the question of human existence. This issue could lead to Gusmen and his paintings being personifications. On the other hand, this could also be Gusmen's offer for the audience to ponder issues of existence.

The feeling of vastness on Gusmen's canvas depicts the sweeping freedom of human existence. However, the horizons, trees, shorelines, firmaments and the presence of doors in his paintings indicate that there is something determinant about freedom. Thus freedom is relative, it has its own limits and boundaries.

Such meditation, of course, still regards the particulars of existentialism in modern philosophy. A question then arises: how free is freedom? In turn, the limits of freedom of each individual will always correlate to the freedom of others. The crowds of figures that demonstrate being "isolated in the base" reflect the fundamentals of this adage - when I require my freedom, I, too, require for the freedom of others. This situation creates irresolvable conflict, because "your freedom limits mine".

As a contemplation, this simple adage - that is comprised within Gusmen's paintings - is in fact still applied and has a context in the midst of various social changes that are occurring in our society today.

Aminudin TH Siregar

Bandung, 17th November 2010

Gusmen has been titling his works "Tamu" ("Guest") for a long time. However, he never determined to present this series of "guests paintings" as a unified whole which would be established into a solo exhibition. All this time, his works entitled "Guest" have been included in other exhibitions he participated in. Out of the numerous works he has created, the "Guests" series has a certain appeal of its own that can elucidate the main points of Gusmen's artistic concept. Therefore, in this year's solo exhibition, Gusmen Heriadi finally presented the title Guests. It is a simple word that corresponds with "traveler", "newcomer" or "visitor." Gusmen and I do not use any of those three words because "guest" induces an enigma or imposes a certain mystery. It has more emotive meaning, eliciting emotions as compared to the other corresponding words that are more "generic." Hence, in addition to being symbolic, the word "guest" also carries a plurality of meanings as well as conveying overlapping issues. It is an umbrella for the various things he uses as materials to expand the discussion. For Gusmen, Guests is also a matter of "arrival" and "departure." It is about someone who "comes" and "goes," invited or otherwise.

Gusmen presents many human figures as the main subject of all his works. The figures are depicted in different poses such as falling from the sky or rolling from behind the trees. In Guest #8 (2008), the naked figures look as if they just arrived (or could be about to go) from or into an alley formed by a wide gap between the trees. The trees are brownish black, as if burned dry. The alley curves into a dark turn. Two white lines at the end of the turn build an illusion in the shape of a small door. The presence of a blue pond does not just add an accent to the painting, but also strengthens the impression of mystery. All of these elements successfully stimulate a layered process of meaning. Guest #8 adopts a naturalist style of painting. Even so, it is not the feeling of beauty or admiration being perceived, but rather an allure to enter the gloomy atmosphere that would negate our emotions towards nature.

In this series, Gusmen also utilizes a background that gives a panoramic impression - a vast desert with a faint horizon line depicted. In Guest #2 (2007), there is a door on the horizon line that runs diagonally. This door creates very strong direction about the origin of an arrival and departure gate for the figures - like a final exit that gives a men a last chance to make a decision. In some cases, such an atmosphere is reminiscent of the waiting room in a terminal at the airport - a worrisome place, because one never knows if we will reach the destination we are headed to. We, in that situation, can just surrender. In Gusmen's painting, concepts of a terminal or airport are replaced with dense forests, vast savannahs, corners of rooms and beaches.

As we see in Guest #9, the figures are suggested to be "floating" above the beach that divides the land and the ocean. Aside from this, he adds a "second background" with three lines that build the appearance of a corner of a room and its door. This layered background gives the illusion of both a world within and an outside world, or as voiced by the late art critic Sudarmadji - "intrinsic" and "extrinsic." These two factors could be used as indicators to help the artist comprehend and assess the "world" around him. We can postpone the in-depth analysis of these two factors to later discussions. However, with this provision, we can generally evaluate that the use of background in Gusmen's paintings invites a layered meaning. This also means that Gusmen pays attention to the background as something important to be studied.

Almost all the figures in his paintings are seen as a clustered mess. But in one or two paintings they seem to form a pattern or specific configuration. In the painting Guest #9 (2008), for example, the configuration is formed into "prayer beads," while in another work we find only one figure. Up to this point, the significance of fragmentary and patterned figures could deviate the discourse of disorder and order. Meanwhile, when the figures are examined one by one, we find that each figure is given a cushion or platform to rest upon and some of them form a comfortable couch. This causes each figure to not be stepping on the earth. These figures and the positioning of them thus develop the idea in our minds of the arrival and departure of "guests."

If Gusmen represents the figure of a post-colonial artist, then perhaps his works are built upon local interest and deal with the questions of identity, history and globalization. Nevertheless, as with several painters in his generation, Gusmen does not urge his art to be a "political statement," nor does he assign art as an instrument for social change as most artists did in the late 1990s. Political arts and social criticism have a strong influence on young artists' practice of art, however Gusmen does not appear to be in this category. His style is sublime rather than provocative.

Amidst the gloom and obscurity of the Indonesian contemporary art scene until the mid-2000s, the debate about contemporary art involved two remaining views which valid arguments had not proven. The first was the assumption that Indonesian contemporary art was identical to arts that had a critical dimension - criticisms directed against the political world and the power of the state. Art in these terms were also identical to the artists' defence against social reality. Works of art by artists were used to not only narrate matters of social pathology but also with a certain awareness that tended to be applied to defend and define the agenda of change for society. Thus, "Indonesian contemporary art", recognized by a handful of art observers, in itself carried the "morality."

Second was the view which agreed that Indonesian contemporary art was identical to the "market." Artists were confronted by the fact that their artworks were nothing more than commodities of the market. This reality potentially restricted the artistic space of artists. Despite this, paradoxically, this fact was discreetly celebrated as well. For those who favored the market, the first argument was viewed to be against reality and they questioned the fundamentals of the assessment of the relationship between the practice of art and morality. Such criticism is then developed by raising a new question: is the morality in this context actually "market morality," which is aligned with ethics and market demand?

Gusmen, who graduated from ISI Yogyakarta in 2005, began his career in the middle of this situation. He was aware that the position of an artist was not as secure as he imagined it to be and realized that the reality he faced was uncertain. He did not exactly favor the "critical arts camp." On the other hand, he did not necessarily support the "commodity arts camp" either. He tried to escape this tension and eventually chose to concentrate on aesthetic explorations. He wanted to explore the potential plane (canvas), and arrange the strength of his painting's character while staying receptive to "influences" that he deemed as worthy to be developed and adapted to his artistic instincts.

Similar to his friends in the Sakato Arts Community and Genta, Gusmen is an artist who chose a different path out of the two previously fixed choices. These artists (traveling artists from West Sumatra) aim to re-establish the "universality of art" but with a belief that is not ultimate nor absolute - just like Western modernist credos. Gusmen believes that it is not his responsibility as an individual to think that art can save the world, though art can actually sustain humanity. In turn, art will reveal identity, reflect culture and form a civilization. That is why he and dozens of other artists in that community welcome any effort that aims to promote artistic discoveries for the development of Indonesian art. To some extent, this attitude managed to minimize the uncertainties of their social status in the field of art. It also frees the artists from a number of determinations and restrictions set by the world around them.

As interpreted by other young artists, in the midst of such apprehension, the term contemporary art is not something that is certain and therefore should be relied upon. Gusmen does not trap himself in that kind of "battle of discourse." He does not compose a strategy let alone formulate a method to be accepted in the "field of Indonesian contemporary arts". For him, such a choice will only confine the artists within unnecessary terminology.

There are other more important tasks young artists should carry out, he feels. Gusmen actively participates in various art exhibitions and continuously promotes different artistic creations. He claims that this is the only way an artist can better understand and deepen his works.

Existentialism

Every young artist who started his career in the art world has at one time or another contemplated his true identity. In the process, he searches for the "differences" and "similarities" between himself and other artists. The results often are a dead end. However, many young artists managed to emerge from this deep reflection and "find themselves."

The discovery of identity is still a process. What is typical about this process is there will always be a personification (embodiment) of an artist through a number of forms in his works. It is not uncommon that an artwork is a personification of the artist. Matters of the "self," "individual constructions" and "the search for identity" are reflected. However, not everything can be deciphered clearly and explicitly which is what makes art interesting. One is saying something that cannot be said. The artist depicts emotions and ideals that are difficult to express normally.

Art is a hiding place from "the self" and presents an artist's "private atmosphere" for others to view. Every artist has a lot of ways to present this "atmosphere." What stands out in Gusmen's works is the strong ability to deliver a vast, grim and quiet "atmosphere" which immediately persuades us to question the "fate" of man as a "guest" in the world. As mentioned, the "background" in Gusmen's paintings holds the same "weight of meaning" as the human figures. Both are equally important because their meanings correlate with each other. This background is not a mere "background to decorate a painting" but possesses deeper meaning.

In conclusion, Gusmen's series of Guests immediately causes us to reevaluate why we come and go, why we must "visit" this world? At this point, we turn to the question of human existence. This issue could lead to Gusmen and his paintings being personifications. On the other hand, this could also be Gusmen's offer for the audience to ponder issues of existence.

The feeling of vastness on Gusmen's canvas depicts the sweeping freedom of human existence. However, the horizons, trees, shorelines, firmaments and the presence of doors in his paintings indicate that there is something determinant about freedom. Thus freedom is relative, it has its own limits and boundaries.

Such meditation, of course, still regards the particulars of existentialism in modern philosophy. A question then arises: how free is freedom? In turn, the limits of freedom of each individual will always correlate to the freedom of others. The crowds of figures that demonstrate being "isolated in the base" reflect the fundamentals of this adage - when I require my freedom, I, too, require for the freedom of others. This situation creates irresolvable conflict, because "your freedom limits mine".

As a contemplation, this simple adage - that is comprised within Gusmen's paintings - is in fact still applied and has a context in the midst of various social changes that are occurring in our society today.

Aminudin TH Siregar

Bandung, 17th November 2010

Stay connected.

Sign up to our newsletter for updates on new arrivals and exhibitions